|

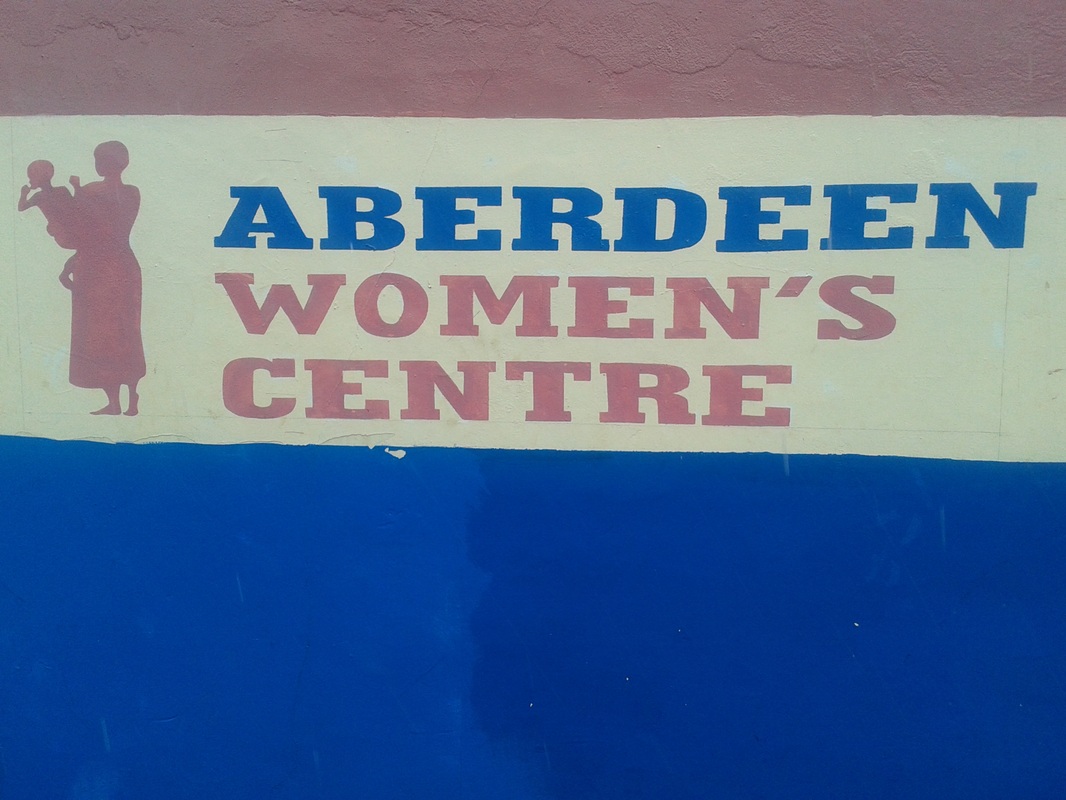

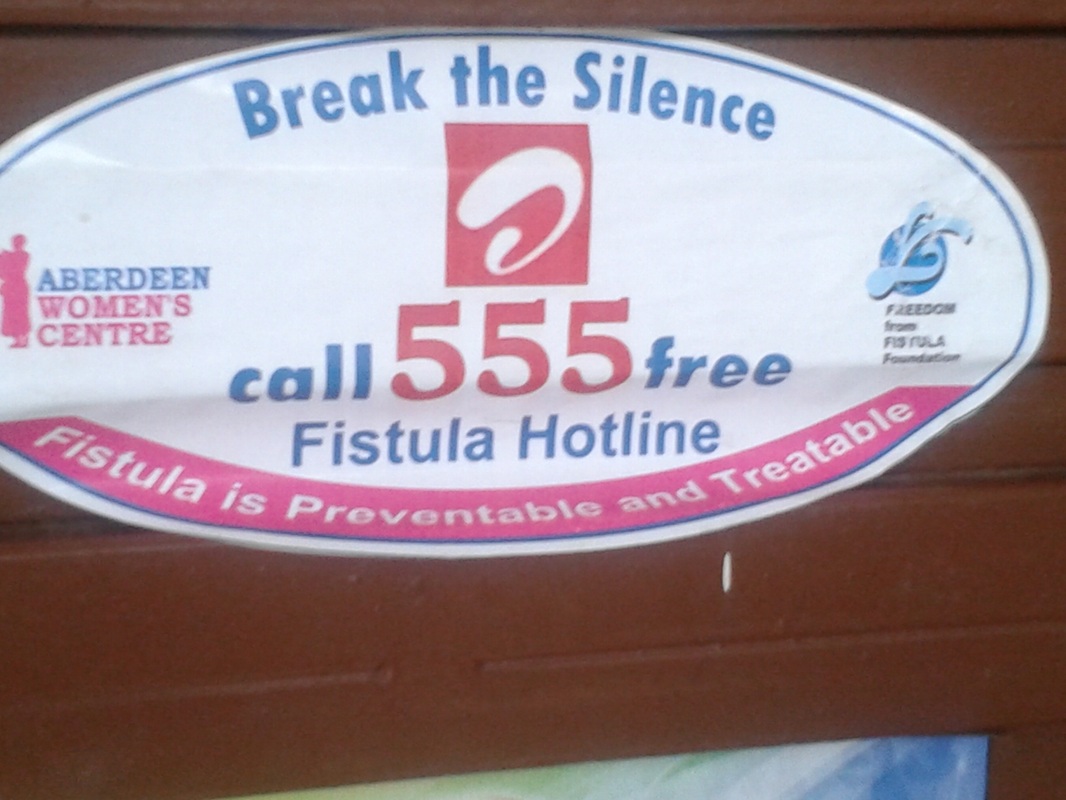

By: Habiba Cooper Diallo This July and part of August, I spent my summer in Guinea and Sierra Leone during which time I had the opportunity to visit a few hospitals and clinics in order to learn more about obstetric fistula in the two countries. Dabola is a Prefecture in north-eastern Guinea, near the Malian border. It’s part of the region known as Haute-Guinee, and consists of a melange of ethnic groups, primarily Mandingo and Fulani peoples. In the last week of my stay in Dabola, a cousin of mine who was completing a summer residency for medical school at the Hopital Prefectoral de Dabola invited me to accompany him to the hospital. I visited twice. On my first day, I shadowed the doctors and some of the trainees, observing patient check-ups, ward visits etc. I later went to the maternity ward—my ward of preference :) —where I encountered a young woman in the process of giving birth. She was having, to say the least, a difficult labour. Apparently, she had not urinated since the day before due to how the baby was positioned in her uterus. Her bladder was thus compromised and the midwife had to use a small container to collect her urine as she pushed gently on her stomach to induce it to come out. At last, she had urinal relief. Soon after, I asked the head midwife, or sage-femme as it is said in French, if there were any patients who presented to the hospital with obstetric fistula. “Yes, there are at times” she explained, “actually, up to this morning, there was a woman with fistula who came to the hospital, but we do not have the capacity to treat fistula patients here, so we had to send her to Kissidougou where there is a team of obstetric surgeons who can operate on her there.” Kissidougou is in the southern part of Guinea about 303 kilometres from Dabola or a 5 hour drive depending on the roads. I noticed that Kiyya, not her real name, was in the birthing room on her own for the most part except when the doctors would go in and try various methods to bring on her contractions. I could not fathom why she had no relatives with her present in the room. There were two older women who had accompanied her. Nonetheless, they seemed quite indifferent to Kiyya’s need for comfort in one of her most biologically and emotionally vulnerable states. I made an effort to visit her continually in order to hold her hand and offer her words of encouragement. When I could no longer go in to stay with her (the doctors sort of banned me because I did not have on a white coat, tongue-in-cheek), I anxiously asked why no one was with her in the birthing room. As her contractions came on stronger, I could hear her crying out in pain as I sat on a bench in one of the hospital corridors. Finally, one member of staff intimated to me that she had a grossesse non-desiree, an unwanted pregnancy; and hence, the treatment from the two older women. Salle D'accouchement- "The Birthing Room" A few weeks following my time in Dabola, I was off to Freetown, Sierra Leone, through a bustling and exciting travel route that began in Guinea’s capital, Conakry. I left from Madina, the country’s largest market. Indeed Madina is an event in itself. Entering by car, as we did, you come up upon a long queue of traffic and begin crawling your way into the market’s core. Once inside, you are solicited by vendors trying to sell you every kind of merchandise from indigo-dyed Fulani cloth, leppi, to bars of soap and schoolbooks. There are myriad cash traders who operate within the interior of the market as opposed to the produce sellers who populate the marker’s exterior. These men are able to change all kinds of currencies from throughout the world into Guinean francs or vice versa. Buy and sell. Sell and buy. After walking around Madina for what felt like hours trying to locate the Melian coach bus that I was to take into Freetown, my cousin and I gave up our search. Defeated, we realized that we had some confusion regarding the days on which the bus departed. I had missed the bus, by one whole day it seemed. Still, I needed to make it into Freetown. As fate would have it, I ended up boarding one of the many minibuses that departed from Madina to capitals all over West Africa—Freetown, Dakar, Bamako, Abidjan etc. This was definitely going to be an adventure. Once we had finally made our way out of Madina, the journey began from Conakry—Cooyah—Faranah—into the verdant, forest vegetation of southern Guinea, which was quite a contrast to the high, temperate plateaux of Dabola (Haute-Guinee), but beautiful all the same—and eventually Freetown. My mind returned to the young lady I met who was in labour at the Hopital de Dabola Freetown, Sierra Leone After a few days in Freetown, Zakiyyah, one of WHOI’s volunteers, facilitated my visit to the Aberdeen Women’s Centre (AWC). The Aberdeen Women’s Centre is a medical facility where fistula patients can receive treatment and other necessary services such as counselling and literacy-training. I received a warm welcome from AWC staff, and was shown around by a Kenyan nurse. They perform between 200 and 230 fistula operations per year and are trying to increase this capacity. In BO, a city three hours from Freetown, there is the West African Fistula Foundation, another site in the country where women can receive fistula repair surgery. The nurse informed me that AWC has many patients from Guinea due to discrepancies in how information is shared between people. For example, if a Guinean fistula patient in a remote community hears that a woman with fistula was successfully treated in neighbouring Sierra Leone, she will then attempt to make it to Sierra Leone for treatment although there are facilities in Guinea. He also told me that several of the patients who came from Guinea were not new fistula cases; in the past, they had unsuccessful fistula repairs by district gynaecologists in their own country. Back in Conakry, I made a visit to the Engender Health office. In Freetown at AWC, I met Dr. Alexandre Delamou who told me that Engender Health ran several fistula initiatives throughout hospitals and clinics in Guinea. At Engender Health, I met Dr. Sita Millimono who spoke with me extensively about the work they were doing in Guinea to eradicate fistula. Their programs in places like Labe and Kissidougou involved key community members like religious leaders and politicians given that the words and actions of such people have the power to influence the way people regard maternal health, pregnancy and childbirth. She told me that their programs were having much success and that the mayor of Kissidougou, for example, was passionately involved in eradicating fistula in his district. He speaks on the radio about the importance of amassing support for fistula and helps in finding host families for newly cured fistula patients who have been living outside of their own families and communities for years upon years. Sometimes it is difficult for fistula patients to return to their own families after having been abandoned by them for so many years. I had a truly educational summer. At the Hopital Prefectoral de Dabola, Aberdeen Women’s Centre, and Engender Health I developed an appreciation for the scope and context of fistula in Guinea and Sierra Leone. My visits to the medical facilities reinforced my belief that maternal health and services deserve way more attention than they currently receive.

As I return home to WHOI, I reflect upon what it means to have access to health care and to adequate medical facilities. I am aware that as a resident of Halifax, Canada, if I were to go into labour I would likely not end up with a hole between my bladder and vagina from which urine would incessantly leak (obstetric fistula), but still, as a Black Canadian woman, I have other concerns and grievances about my access to quality medical services in a first world country. I am entering my final year of high school this September and I intend for WHOI to create a link between the health needs of African-descended women living in Halifax and the experiences of women who suffer from fistula on the African continent. It is true that fistula has no borders nor temporal designations. From Ethiopia to Guinea and Sierra Leone in the 21st century, fistula patients still ask for justice to be done to their cause as Black slave fistula patients once did in 19th century America as did women in Egypt’s Pharaonic age.

3 Comments

Fana

3/12/2015 11:30:39 am

You are an incredible young woman and you have a way with words, just like your mother. I learned a lot. Thank you,

Reply

Habiba

3/13/2015 01:55:08 am

Thank you Fana :)

Reply

Thanks for bringing awareness to this situation .You're an amazing ..I was enlightened. Blessings as you continue on your journey.

4/17/2015 01:40:37 pm

Reply

Leave a Reply. |

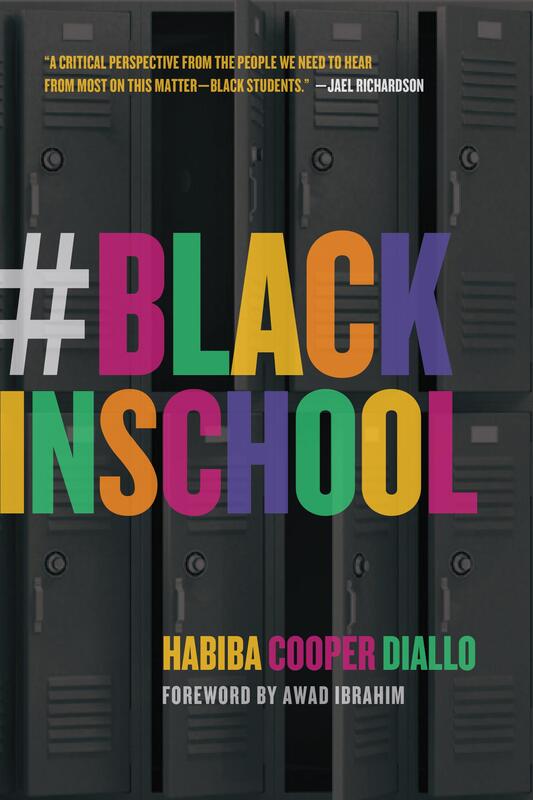

Habiba DialloI am a Canadian end fistula advocate, author, and the founder of the Women’s Health Organization International, WHOI. I have been doing fistula awareness-building in Canada for the past 15 years. Get in touch here CategoriesArchives

March 2023

|

NEW BOOK

|

FOLLOW ON SOCIAL MEDIA...

|

|

© 2024 Habiba Diallo. All rights reserved.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed